Morton Feldman, "King of Denmark" (1964)

Contrastingly, Penderecki uses elements of graphic scoring to show pitch continuum locations more specifically than traditional notation can.

Penderecki, "Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima" (1960): specificity through

combination of traditional and non-tradition notational ideas

Graphic notation also creates an easy bridge between two worlds of art, which is, in my opinion, a very good thing. The world of artists often has unfortunately strong imaginary borders, so opportunities to bridge these borders are great. This is a great way to rope visual artists into becoming composers, rope composers into becoming visual artists, interesting performers more deeply in visual arts, and more. The other wonderful thing is that you don't have to be deeply entrenched in any area(s) of the art world to dive into graphic notation. If you have no background in the arts but a definite interest, you can make a graphic score. All you need is a musician friend (or generally artistically adventurous non-musician), and your work of art can be realized. Bridging all these borders is fun and can open one's eyes suddenly into areas someone in our field might not necessarily bring us.

Speaking as a music student, I wish all music students spent at least a little time interpreting and working on graphic scores. When I play them, I often quickly stagnate in my ideas for interpretation, and my creative mind has to go on overdrive in order for me to keep my performing interesting to myself. This has done wonders for my improvising skills, and I think it would be a fantastic mental and artistic exercise for all musicians to undergo.

Unfortunately, I have not worked much yet with graphic scores. I have only premiered one work for graphic score (Kayleigh McKay's "The Viola Tango" (2012/13), for solo performer playing viola). I have looked through some others, read through a couple, and seen many performances of many works. My favorite experience with alternate notation has been performing Cornelius Cardew's "The Great Learning" as part of Make Music New York 2013. One major aspect of Cardew's work that I love is that it explores a wide variety of notational systems: traditional notation, purely graphic scoring, a halfway point between the two, instructional scoring, and more.

Cardew, "The Great Learning" (1971), Paragraph 1

semi-graphic notation in top and middle parts; fairly traditional notation on bottom (organ) part

Cardew, "The Great Learning" (1971), Paragraph 6

instructional score

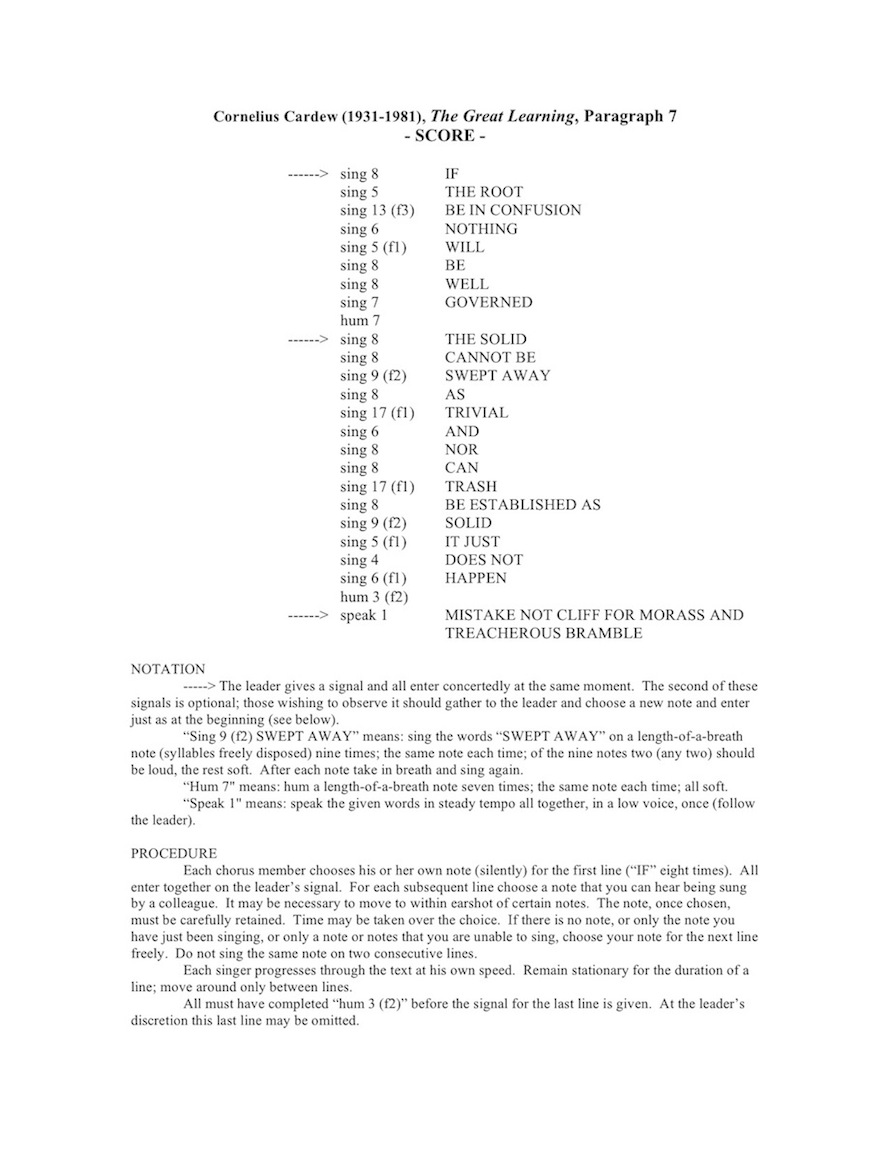

Cardew, "The Great Learning" (1971), Paragraph 7

instructional, with light elements of graphic scoring

In this work, every movement was a very different challenge to decode, and that was where much of the fun was. Each movement was a new experiment and a new experience, and brought a new sense of playing, often through the vast differences in notation.

Having said all this, I'll be honest: I've had much more fun with my experiences in instructional scores than with graphic scores. Having worked on Wolff's "Sticks" and "Stones," various movements of Cardew's "The Great Learning," premiered a work for solo performer in offstage closet (Alex Cronis's "The Day We Stopped Talking," 2013), read through Tim Feeney's "Still Life," and written a couple small instructional works myself, I've taken more out of these and felt like I was able to make better performances. I'm not certain about why. Perhaps I'm reticent to improvise when given too much context of how to do it (specific durations, contours, etc; needing to adhere to a score in time), and prefer to improvise when given more freedom. I'd say I definitely enjoy being able to study a set of instructions in great depth, make a detailed plan about my realization of it, then just go without having to stick constantly to a score in front of me. Instructional scores, like graphic scores, can connect us to other arts (writing), as well as roping in non-musicians (who need only know how to read and write in a language in order to compose such music, and often to perform it as well).

Finally, I'd like to briefly address the question of labeling graphic scores: is the "composer" really a composer? Is the performer the composer? Who writes the music? I'd like to submit that these questions don't matter. I think this is a point where labeling becomes a hindrance to discussion. Labeling should exist to clarify discussion and debate; however, in this case, we do not need to answer these questions in order to communicate clearly about this art and our opinions on it. I don't care whether I should call the writer of the score a "composer," "facilitator," or just "artist"; I don't care whether I should call the performer a "composer/performer" or perhaps "realizer." I care whether I find it interesting and worthwhile, and why; and I care whether someone else finds it interesting and worthwhile, and why, so that we can discuss it. The rest of the answers to such questions would only distract the conversation from the actual art at hand.

No comments:

Post a Comment