Community School of

Music and Arts

Ithaca, NY 2/27/14, 8

pm

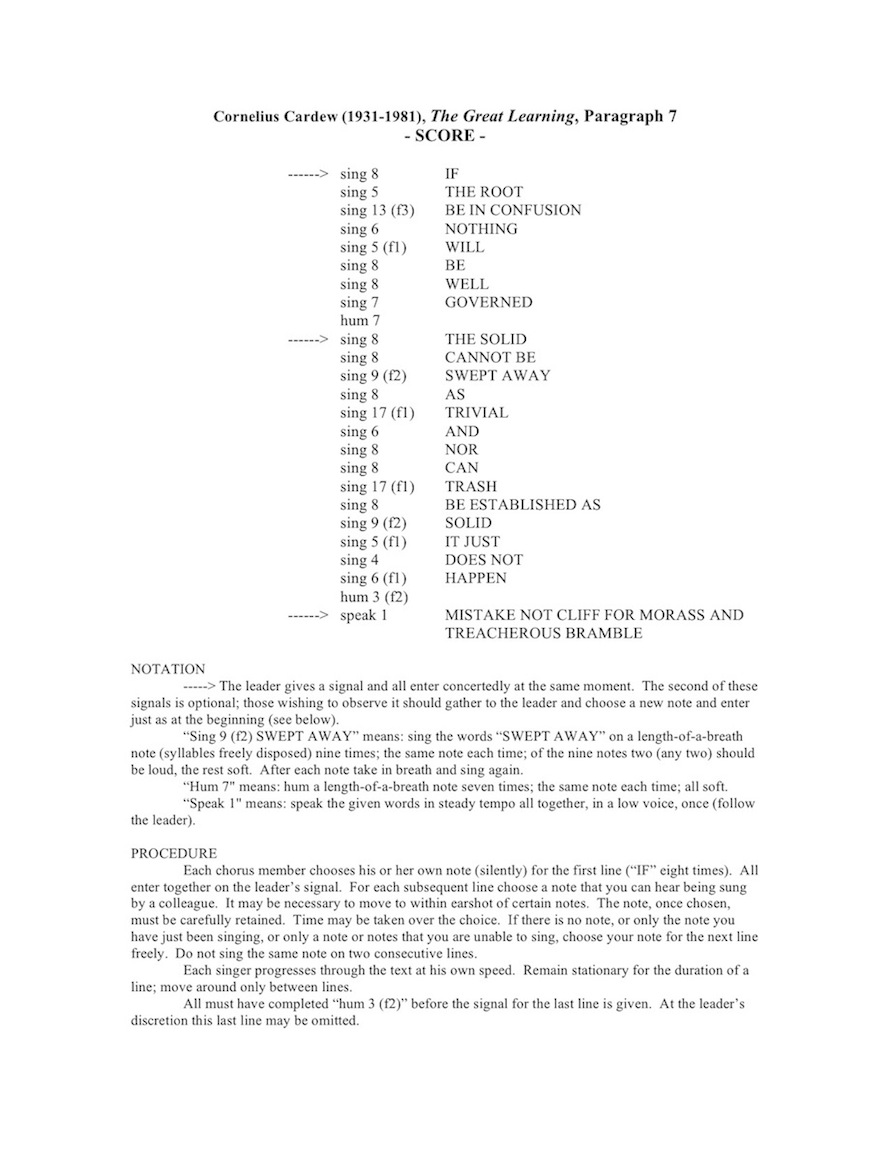

Nick moved to Ithaca just a few months ago from Austin, TX, where he was deeply entrenched in the experimental music scene. He owns and operates Weighter Recordings, which releases a variety of long, textural experimental music like his, and is a member of the percussion trio Meridian. He studied for his Master of Music degree with Steve Schick, regarded worldwide as the number one expert in multiple percussion music, and this intense concert percussion background clearly shows in Hennies’ care, performance atmosphere, and attention to extreme detail. I was fortunate enough to meet Nick last summer, when he directed a full performance of Cornelius Cardew’s massive work The Great Learning as part of Make Music New York 2013. Taking part in this brought me to see Nick’s artistic voice, and I knew he was someone worth watching for in the future.

For his debut concert in Ithaca, Nick performed a bipartite program. Each half consisted of the program for an album he has recorded. The first half was the program for his most recent album, “Duets for Solo Snare Drum” (Weighter Recordings, 2013), and the second half of the concert consisted of the program from his release “Psalms” (Roeba, 2010). The “Duets for Solo Snare Drum” are three solo works for snare drum accompanied by another element. Two are accompanied by a non-performative element: silence (Cage’s “One4”) and static noise (Ablinger’s “Snare Drum and FM Noise”); and one is accompanied for part of its duration by three other drone/noise-producing performers (Hennies’ own “Cast and Work”).

The Cage work was classic Cage, inviting the audience to listen to individual, discrete sounds with silence between each. Hennies demonstrated some unique methods of drum sound production. For example, he placed a long, thin metal object with one end on the head and one end hanging over the edge, then bowed the portion hanging off the drum to produce resonant frequencies of both the object and the drum. Ablinger’s work for snare and static noise was a one lone texture of snare drum, excited by the hands, blending its timbre into amplified radio static and alternating with periods of silence. This was perhaps the least effective work of the concert for me, as the snare drum seemed to make little difference to the work, and only served to visually distract from my concentration on listening to the static.

Hennies’ work “Cast and Work” is a 25-minute roll on the drum, snares off, with fixed media component consisting of a nearly unchanging drone. This is the work on the concert that took me by surprise and threw me for a loop. Hennies roll invited me into a sound world of constantly shifting emphases on different overtones of the drumheads and their interactions with the drone. The head sound reverberated around the large, resonant room, and as it did so, irregular sustains began to emerge. I was brought into a deeply meditative state, as I believe is an intended result of the music. Finally, 15 minutes into the roll, the three other musicians entered. One played a rebab (bowed Gamelan string instrument), one played a tin can, and one manipulated a fascinating noisemaking contraption of cymbals perched atop tensed spring coils. These were used as repetitive noise producers. As a listener, I am NOT normally one to attach my own narrative to pieces that do not explicitly have intended, grounded narrative. Having said that, I was shocked to find an immediate, narrative response the instant the other musicians entered. Suddenly, I was on the production floor of a factory or mill, with all the machines humming, whirring, whining, and rattling around me. The snare drum and fixed media were the general hum of the constant unchanging machinery (perhaps heating or cooling), while the other three musicians represented the regular repetition of cyclically acting machines. I found myself suddenly transported to this world, and after several minutes of it with my eyes closed, I managed for several seconds to really believe that I was simply in a factory, production whirring along full steam ahead, while I enjoyed the steady noises of the industrial equipment.

The second half consisted of five works, all directly based on Alvin Lucier’s famed “Silver Streetcar of the Orchestra” for solo triangle. Each work was for one solo percussion instrument (vibraphone, snare drum, woodblock, triangle, vibraphone again). Lucier’s work was included, and the other four were composed by Hennies. All followed the compositional design of the Lucier, with moderately fast constant notes used to highlight gradual changes in timbre. Hennies transitioned without pause from each piece to the next, which was effective in connecting them sonically and ideologically.

Particularly of note was Hennies’ “Psalm 1” for vibraphone. As Hennies hammered away at the barrage of notes, the instrument’s sustain echoed around the wonderfully reverberant room. The damper was removed from the instrument altogether. Sustained sounds came in irregular waves, sometimes instantaneously, sometimes for several full seconds before receding into only attack sounds. Different overtones came to light, and would occasionally overpower those normally audible on the instrument. This was sometimes due to Hennies’ careful stroke placement on the bars, and sometimes simply due to chance echoing and my ear’s tendency to wander across different overtones when hearing one sound repeatedly for so long. What I know for certain is that I heard different aspects to the vibraphone’s sound that I haven’t properly listened to before. The works for snare drum and woodblock were also effective, and the Lucier was fascinating as always. Ending on vibraphone brought obvious but satisfying cyclical unity to this half of the program.

Hennies plans to put on at least several concerts per year. Some will be shows by other musicians or groups (he’s bringing organ and electronics duo Coppice on March 21), and some will be solo shows for him. I look forward immensely to whatever Nick plans to put on in town; he has a distinctive and worthwhile voice that is a welcome addition to Ithaca’s ever-eclectic music scene.

Nick Hennies: http://www.nhennies.com

Weighter Recordings: http://www.weighterrecordings.com